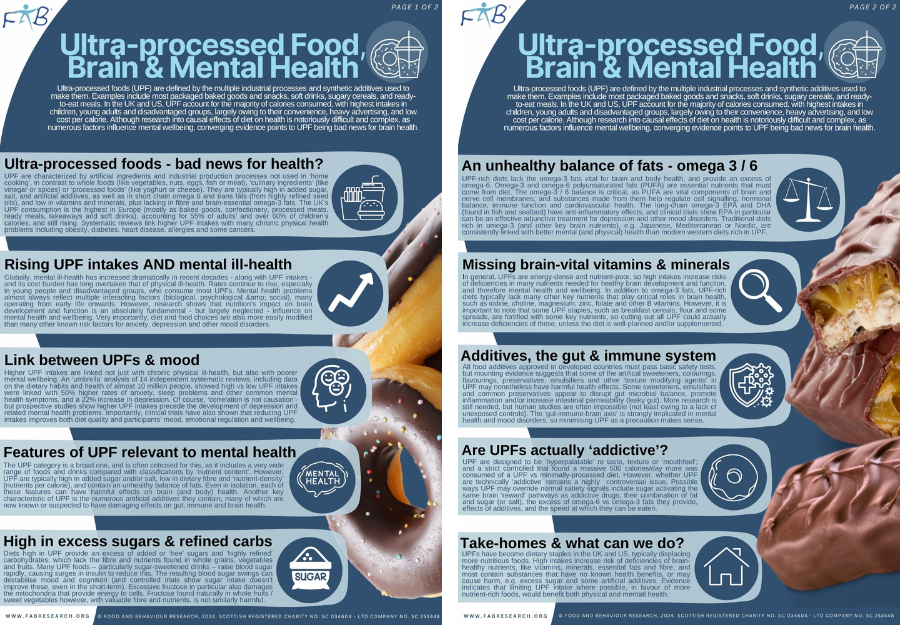

Ultra-Processed Food and Mental Health

'Ultra-processed foods' (UPF) are almost never out of the news. And while some articles and books suggest they should all be avoided at all costs, others tell us that there’s really nothing to worry about.

Here we outline what UPFs are, and what research is showing about the impact of high UPF intakes on mental health and wellbeing.

As usual, there are no definitive answers - and plenty of questions that still need addressing. But for anyone wanting to make informed decisions about something as fundamental as the food they eat - or feed to others - being aware of some of the key issues that current evidence is highlighting is important.

What are ultra-processed foods, or 'UPF'?

UPFs are defined by the multiple industrial processes and synthetic additives used to make them. They are characterized by artificial ingredients and industrial production processes not used in ‘home cooking’, in contrast to whole foods (like vegetables, nuts, eggs, fish or meat), ‘culinary ingredients’ (like vinegar or spices) or ‘processed foods’ (like yoghurt or cheese).

Examples of UPF include most packaged baked goods and snacks, soft drinks, sugary cereals, and 'ready-to-eat' meals - as well as 'takeaway' foods and the majority of meals now served in cafes and restaurants in the UK, US and many other developed countries.

In the UK and US, UPF now account for the majority of calories consumed. The UK’s UPF consumption is the highest in Europe (mostly as baked goods, confectionery, processed meats, ready meals, takeaways and soft drinks), accounting for 55% of adults’ and over 60% of children’s calories.

Children, young adults and disadvantaged groups are the highest consumers of UPF, largely owing to the convenience and universal availability of these compared with whole or minimally processed foods, their relatively low cost per calorie, and the heavy advertising targeted at these particular groups.

Mental ill-health and UPF intakes have increased together

Globally, mental ill-health has increased dramatically in recent decades - along with rising UPF intakes - and the associated cost burden has long overtaken that of physical ill-health, although this too has continued to rise.

The prevalence of mental health problems has risen particularly sharply in children and young people and disadvantaged groups, who are also the highest consumers of UPFs.

Of course, 'correlation is not causation'. Mental health problems almost always reflect multiple interacting factors - biological, psychological and social - and these all continue to operate throughout life.

However, early life and adolescence are known to be particularly critical periods for shaping brain development, and therefore risks for developmental or mental health conditions. Furthermore, the impact of nutrition on brain development and function is an absolutely fundamental influence on mental health and wellbeing at any age - albeit one that is still largely overlooked or ignored.

Very importantly, diet and food choices are more easily modified than many other known risk factors for child behaviour and learning difficulties like ADHD or autism, or mental health conditions like anxiety, depression and other mood disorders, or dementia.

Ultra-processed foods - bad news for mental health?

Research into causal effects of food and diet on any health outcomes is notoriously difficult and complex - and this is particularly true for outcomes concerning mental health. Even defining, diagnosing and measuring most psychological or psychiatric condtions can be difficult enough, and numerous different factors always interact to influence our mood, behaviour, wellbeing or mental performance.

However, converging evidence from numerous sources points to UPF being bad news for brain health.

UPF are typically high in added sugar, salt, and artificial additives, as well as in short chain omega 6 and trans fats (from highly refined seed oils), and low in vitamins and minerals, plus lacking in fibre and brain-essential omega-3 fats.

Systematic reviews have consistently linked higher UPF intakes with many chronic physical health problems - including obesity, diabetes, heart disease, allergies and some cancers - and also with significantly shorter life expectancy in general, controlling for other factors.

Link between ultra-processed foods & mood

Higher UPF intakes are reliably linked not just with chronic physical ill-health, but also with poorer mental wellbeing.

An ‘umbrella’ analysis of 14 independent systematic reviews, including data on the dietary habits and health of almost 10 million people, showed high vs low UPF intakes were linked with 50% higher rates of anxiety, sleep problems and other common mental health symptoms, and a 22% increase in depression.

Again, association studies alone can't establish cause and effect - and obviously, mental health problems may be a cause, as well as consequence, of poor diets. But importantly, prospective studies show that higher UPF intakes precede the development of depression and other mental health problems.

Most importantly, controlled clinical trials - which can demonstrate causality - have shown not only that reducing UPF intakes can improve the nutritional quality of participants diets, but also that this leads to better mood, emotional regulation and wellbeing.

Features of ultra-processed food relevant to mental health

The UPF category is a broad one, as it includes a very wide range of foods and drinks compared with classifications by ‘nutrient content’. However, most UPF also share many common nutritional features. They are typically high in added sugar and/or salt, low in dietary fibre, contain an unhealthy balance of fats, and have low ‘nutrient-density’ (nutrients per calorie) - increasing the likelihood of essential nutrient deficiencies.

Even in isolation, each of these nutritional features can adversely affect brain (and body) health. If the whole diet is high in UPF, the negative effects of these features in combination will be magnified. Some UPF have more nutritional value than others, but none are essential, and real foods are always the best way to obtain essential nutrients whenever possible.

Another key characteristic of UPF is the artificial additives they contain - such as preservatives, sweeteners and other flavourings, artificial food colourings, and emulsifiers or other 'texture modiying' agents.

Again, some UPF contain fewer of these than others, but when analysed, most UPF-rich diets provide a remarkably high daily intake of synthetic chemicals that have never been tested in combination for their safety - nor for their effects on either the gut microbiome or brain function.

Many of these additives are now either known or suspected to have damaging effects on gut microbial balance, immune function and brain health - all of which are interconnected.

What's more, aspects of 'ultra-processing' itself can also affect the way that nutrients are actually absorbed and metabolised.

Accumulating evidence from many sources therefore undermines the simplistic argument that classifying foods by production method 'makes no sense'.

High in excess sugars & refined carbs

Diets high in UPF provide an excess of added or ‘free’ sugars and ‘highly refined’ carbohydrates, which lack both the fibre found in whole grains, vegetables and fruits (important for gut health), and the nutrients that these unrefined sources of carbohydrate would provide.

Many UPF foods – particularly sugar-sweetened drinks – raise blood sugar rapidly, causing surges in insulin to reduce this. The resulting blood sugar swings can destabilise mood and cognition. What's more, the idea that sugar improves mood even in the short-term turns out to be a myth, a systematic review has shown.

Excessive fructose in particular damages the mitochondria that provide energy to cells, as well as contributing to the metabolic problems associated with type 2 diabetes, obesity and cardiovascular disease.

The fructose found naturally in whole or minimally processed fruits or sweet vegetables, however - along with valuable fibre and nutrients these contain - is not similarly harmful.

High sugar intakes are reliably associated with impairments of mood, behaviour and/or learning and memory in the general population, and are also strongly linked with almost all developmental and mental health conditions. Animal studies indicate many of these links may be causal - but as usual, ethical and practical obstacles limit definitive evidence in humans.

An unhealthy balance of fats - omega 3 / 6

The brain is 60% fat - so the type of fats that our diets provide is critical for healthy brain development and functioning.

The most important fats for brain health are the Omega-3 and omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA). These are essential nutrients - like vitamins and minerals - so both types must be provided by our diets. However, the relative balance of omega-3 / omega-6 fats is critical for both brain and body health - particularly with respect to the long-chain fatty acids of each type (known as LC-PUFA), which are the biologically essential forms.

Modern UPF-rich diets are very seriously lacking in omega-3 fats, and provide an excess of omega-6 from highly refined seed oils when compared with any tradional, pre-industrial diets. (They also contain high levels of saturated and artificial fats, some of which are toxic).

Omega-3 and omega-6 LC-PUFA are key stuctural building blocks of brain and nerve cell membranes, involved in all aspects of cell signalling. What's more, a huge number of different substances made from long-chain omega-3 and omega-6 fats play vital roles in regulating hormonal balance, immune function, blood flow and gene expression.

The long-chain omega-3 EPA and DHA (found in fish and seafood) have anti-inflammatory effects, and help to maintain a healthy heart and circulation. Traditional diets rich in these omega-3 (and other key brain nutrients), such as Japanese, Mediterranean or Nordic diets, are consistently linked with better mental (and physical) health than modern western diets rich in UPF.

The relative omega-3 deficiencies that UPF-rich diets create are strongly linked with heart disease, immune disorders and physical health problems, as well as developmental and mental health conditions of all kinds.

Numerous clinical trials now show that increased intakes of the long-chain omega-3 EPA and DHA can have benefits for many aspects of mental health and wellbeing. This evidence is strongest for clinical-level depression and other mood disorders, for which systematic reviews show that EPA in particular (at 1-2g/day) is an effective 'add-on' to standard treatments - as documented in evidence-based practice guidelines developed by a consensus of leading international researchers and clinicians:

Missing brain-vital vitamins & minerals

In general, UPFs are 'energy-dense and nutrient-poor', so diets high in these kinds of foods (and drinks) increase the risks for deficiencies in the nutrients needed for healthy brain development and function, and therefore mental health and wellbeing.

ln addition to omega-3 fats, UPF-rich diets typically lack many other key nutrients that play critical roles in brain health - such as iodine, choline, magnesium, zinc, folate and other B vitamins, among others.

However, it is important to note that some UPF 'staple foods', such as breakfast cereals, flour and some spreads, are fortified with some key nutrients.

This means that cutting out all UPF could actually increase nutrient deficiencies for some individuals and groups, unless the diet is very well-planned and/or supplemented. Examples may include people on low incomes who rely on these foods for their low cost and/or convenience; or highly selective eaters, whose food preferences can be very resistant to change. '

Additives, the gut & immune system

A key defining feature of UPF is that they contain numerous artificial chemical additives that are not found in 'home cooking', nor in minimally processed foods, such as artificial colourings, sweeteners and other synthetic flavourings, emulsifiers (and other 'texture-modifying agents'), and preservatives, among others.

Mounting evidence suggests that many of the additives found in UPF can have harmful effects on gut, immune and brain health, even in isolation - let alone in the multiple combinations to which consumers are routinely exposed.

All food additives approved in developed countries must pass basic safety tests - but these have many limitations, including that each substance is considered only in isolation, and toxicity testing does not include effects on brain function or mental health.

Some artificial food colourings have long been shown - via numerous randomised controlled clinical trials - to adversly affect behaviour and attention in children (as well as physical health problems in some cases).

Similarly, extensive and growing 'real-world' evidence now strongly suggests that chronic use of artificial sweeteners may actually promote weight gain and associated metabolic problems, despite their lack of calories (and in contrast to the apparent benefits shown by short-term clinical trials).

Ways in which many sweeteners, emulsifiers and preservatives widely used in UPF appear to be harmful to health include their ability to (1) disrupt normal gut microbial balance (2) promote inflammation and/or (3) increase intestinal permeability (leaky gut) - and these negative effects are usually mutually reinforcing.

More research in this area is still needed, but controlled trials in humans are often not possible for ethical or practical reasons (not least owing to a lack of unexposed controls).

Given that the ‘gut-immune-brain axis’ is now very strongly implicated in most developmental and mental health conditions - particularly those involving anxiety or mood issues - this evidence would suggest that minimising UPF as far as possible would be a sensible precaution for those affected by such conditions.

Were you expecting a paywall?

Food and Behaviour Research relies on donations to make articles like this one freely available.

Make a quick and easy donation of ANY AMOUNT and help support our Charity to create future articles and resources.

All donations are very gratefully received

Thanks so much for your support

Contact Us

Are ultra-processed foods actually ‘addictive’?

UPF are designed to be ‘hyperpalatable’; and the food industry dedicates huge amounts of research to making sure that their taste, texture or ‘mouthfeel’ is optimised to make consumers want more.

Whether UPF are technically ‘addictive’, however, still remains a controversial issue - not least because of how the term 'addiction' is defined. There are both behavioural and biochemical aspects to addictive behaviours - and importantly, individuals differ in their susceptibility to these. (Not everyone who consumes alcohol regularly becomes addicted to it - and the same is true of highly addictive drugs like opioids).

The key issue is whether specific characterics of ultra-processed foods themselves can be shown to cause 'addictive' or other disordered eating behaviours. This remains an active area of research, debate and controversy, but evidence from multiple sources has been accumulating steadily - and a consensus of leading experts in the field argues that UPF should be regulated in the same way as substances such as alcohol and tobacco that are acknowledged to be both toxic, and addictive.

Certainly, UPF-rich diets are strongly associated with overeating in general, many forms of eating disorders, and obesity (and related health conditions). These links are consistent over time, between countries, and within groups of otherwise similar individuals. However, 'correlation is not causation' - so additional evidence is always needed. Similarly, animal studies support the idea that UPF have 'addictive qualities' - but of course, that kind of evidence cannot reliably be generalised to humans.

To provide definitive evidence of cause-and-effect, 'randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials' are regarded as the 'gold standard'. Human randomised controlled trials (RCT) of any full diets are difficult enough (blinding and compliance being rather harder to achieve with foods and diets than supplements or drugs). But nutritional matching of UPF and minimally processed diets is extremely difficult to achieve.

However, the first rigorously designed and conducted trial of this kind showed that a UPF vs minimally-processed diet (nutritionally matched with great care) led healthy adults to consume a massive 500 calories/day more - leading to almost 1 kg of weight gain within just 2 weeks.

These are obviously very striking findings, and add important support to the proposal that UPF may have 'addictive qualities'.

Of course, replication studies are always needed. And a small randomised, open cross-over trial of adults - patients with overweight or obesity - recently reported that a UPF vs non-UPF diet (nutritionally matched for macronutrients) led to more than 1kg of weight gain in just one week, with more than 800 calories/day consumed (and with fewer 'chews' per calorie).

Again, the group difference observed was simply huge, but further, larger RCTs are still awaited.

- Meanwhile, other studies have already identified many possible ways that UPF may cause overeating by overriding normal signallling of 'satiety' (fullness). These include

- sugar activating the same brain ‘reward’ pathways as addictive drugs;

- the combination of fat and sugar (or fat and salt) that characterises most UPF;

- the excess of omega-6 vs omega-3 fats they provide;

- effects on appetite of some of the additives they contain;

- and also the sheer speed at which UPF can be - and often are - eaten (less chewing is needed owing to their lack of fibre, but other features of their taste and texture have also been deliberately designed by producers to make UPF 'more-ish')

Clearly, it remains to be seen whether (let alone when) any governments or other organisations may decide that there is enough scientific evidence to support the argument that 'UPF' as a food category really are 'addictive' - and to take regulatory action accordingly.

Take-homes & what can we do?

UPFs have become dietary staples in the UK, US and other developed countries, typically displacing more nutritious foods.

High intakes increase risks for deficiencies of brain-healthy nutrients, like the essential omega-3 fats, vitamins, minerals, and dietary fibre. In addition, most UPF contain substances that either have no health benefits, or can cause harm, such as excess sugar and some artificial additives.

Strong associations between high UPF intakes and almost all forms of chronic ill-health are now well-documented; and preliminary evidence from controlled trials shows that even in the very short-term, UPF promote overeating, obesity and metabolic problems.

All the evidence from these different sources points to the same conclusion - that limiting UPF intake whereever possible, in favour of more whole or minimally processed foods, would improve the nutritional quality of most people's diets, and benefit both physical and mental health.

The strength and consistency of this evidence has already led both medical health professionals and leading researchers to call for effective public health policies to regulate and reduce UPF consumption as a matter or urgency.

Given the dominance of UPF in modern, western-type diets - and our global food systems - reducing UPF intakes is of course much easier said than done.

Excluding all UPF is simply not realistic for most people in the UK, US and many other countries - but a healthy and well-balanced diet need not require their total exclusion. The 'UPF' category covers a very wide range of different foods; and some of them are more nutritious, and contain far fewer additives, than others.

Equally, however, UPF themselves are not essential. Reducing our dependence on these foods is perfectly possible (and could also have significant economic and environmental as well as health benefits). However, it does require a re-evaulation of the way we currently produce, consume and value food.

This is likely to be more of a challenge in some countries (including the US and UK, where UPF make up a majority of foods consumed) than in others, whose traditional food cultures have not yet been completely swept away by the rise of UPF - including Brazil, where the NOVA classification system that introduced the UPF label was devised:

Further information

Get information about UPF's straight to your inbox

We will also send you information on other FAB topics that might interest you or others you know and send you our regular e-newsletter which rounds up topical news items around Food and Behaviour.

More articles